Open any investment document or brochure and you are likely to see the following disclaimer somewhere at the bottom of the page: “Past performance is not a guarantee of future results”.

It’s a reminder that history is filled with stories of those who lost money because they believed that if an investment had recorded strong profits in the past, it would continue to do so indefinitely.

The predictability of stock returns

Why is it our natural tendency to extrapolate trends? And is there any evidence that it could be a costly mistake when investing?

The first question is hard to answer.

Behavioral sciences have proposed many theories as to why we tend to assume that recent experiences will continue into the future. Is it a useful heuristic or the relic of a primal brain?

Let’s leave the debate to the experts and simply acknowledge that we humans are subject to extrapolation bias.

When we see a company, a market, or an investment opportunity that has posted a good performance in recent months, in the absence of bad news, it is a natural tendency to assume that the performance will continue at the same pace.

Let’s turn instead to the second question. A fundamental one in my view.

One of the strongest held beliefs amongst the investment community is that over the long term, markets tend to go up because it is what they’ve been doing over the past centuries.

But isn’t this the very definition of extrapolation bias?

The assumption of market long-term growth

If the disclaimer is true, then we are potentially in trouble, because many investors have built their investment processes around that assumption of market long-term growth. Are we doomed?

Not yet. Let’s look at these two contrasting points:

- Markets tend to go up in the long run.

- Past performance is not an indication of future results.

These are not necessarily contradictory. In fact, they depend on two parameters:

- The time horizon you are considering.

- How diversified the market is that you are looking at.

Let me explain.

If we consider one of the most elementary units of economies – companies – their journey is time-bound by nature. They are born, they grow, and they mature. With the exception of a few longevity records, the average lifetime of a listed company is estimated at 14 years.

Daring to extrapolate a single company and assume it will grow indefinitely is a dangerous bet.

If you consider multiple companies at the same time, that’s a different story, because you are aggregating companies that are at different points in their journey. And the more businesses you invest in, the more you get something that looks like an economy.

Even if a few companies in your sample go bankrupt, you can hope that a few successful companies will emerge and compensate for the lost growth.

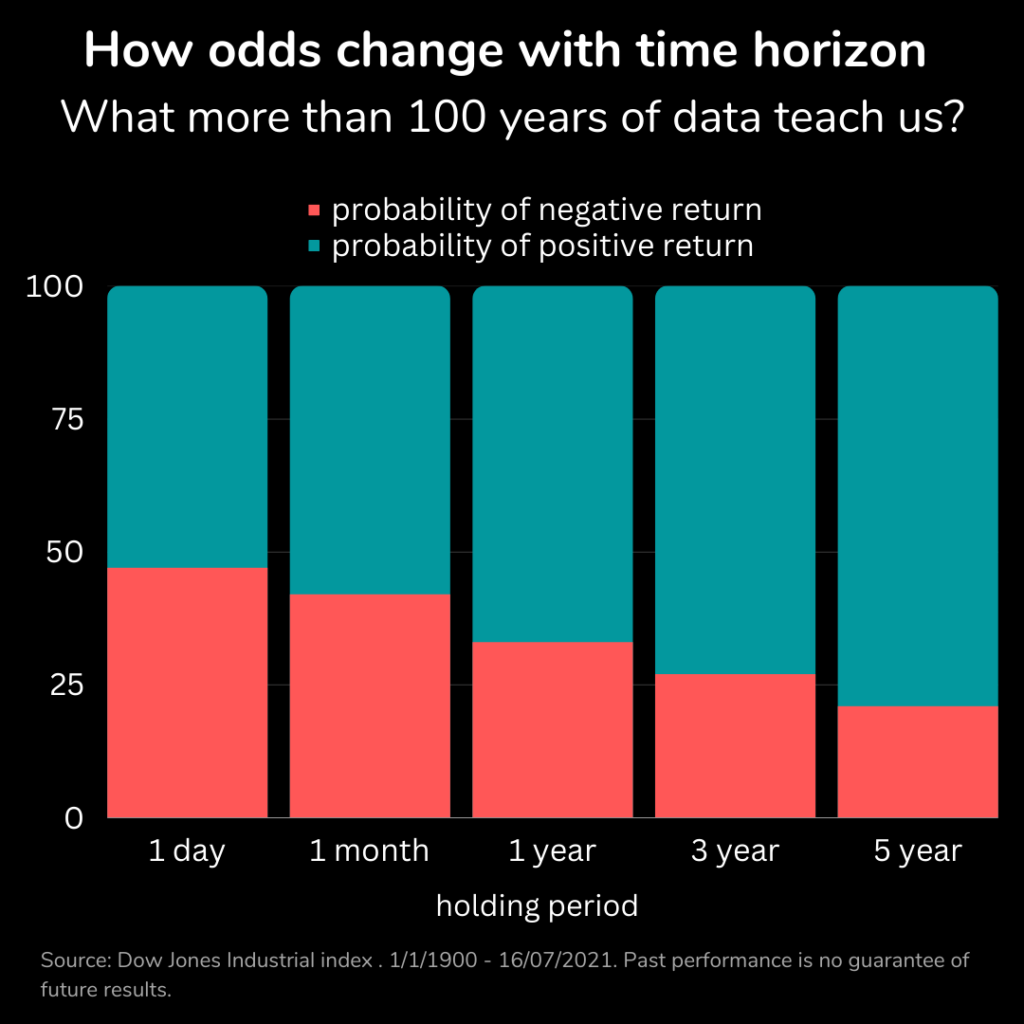

In short, diversification works in your favor if you want to extrapolate. And investing with longer time horizons does, too. Both reduce the odds that things go wrong.

Consider the chart below that shows the probability of losses and gains over different periods of time for a diversified basket of US stocks.

But what about short term extrapolation?

This doesn’t mean that short-term turbulence doesn’t happen.

Over short periods of time, markets can experience sharp fluctuations but still trend up over the long term.

Economies know periods of expansion and contraction under the influence of several factors (population, innovations, capital, war, policies, etc.). These are what economists refer to as “cycles”.

While cycles are not as regular and predictable as we would like them to be, there are fundamental reasons why they are happening.

Take a successful company as an example: As it grows, it tends to attract workers, investors, and competitors that in turn will change the nature of that company or the environment it is operating in. Preserving productivity, margins, and the capacity to innovate is not straightforward, so it is fair to expect bumps.

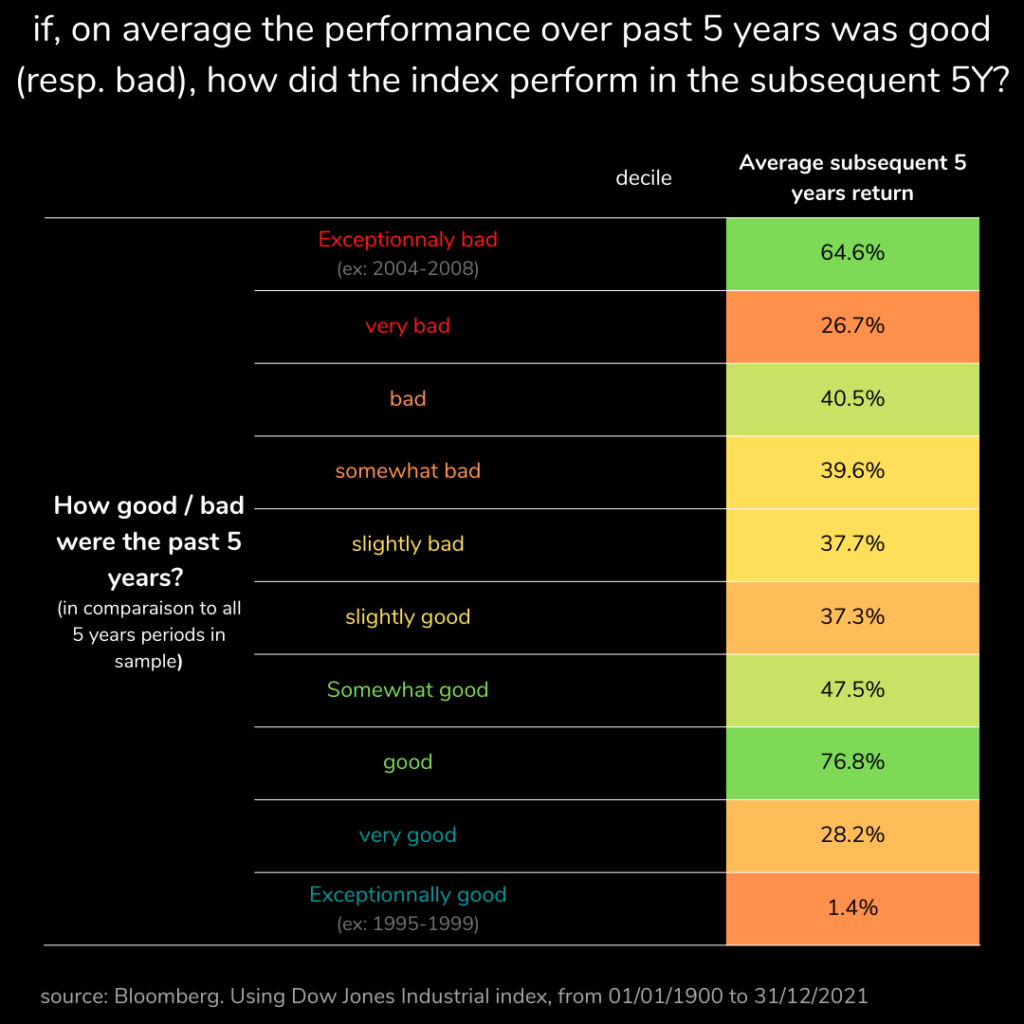

The same happens at the economic level. Excessive inflows and outflows of money can exaggerate market movements. Extremely good periods of investment returns are often followed by poor periods, and vice versa. That’s why in a shorter time frame, extrapolation is tricky.

We looked at the past performance of the same basket of US stocks we used previously and saw if it could be used as a guide for future performance. The chart below illustrates this:

The answer is not really. In fact, the worst periods are often followed by the best periods and vice versa, supporting the claim of the disclaimer. As for good and bad periods, there is no clear indication.

What do we make out of this?

First, proper due diligence of the businesses/markets you are planning to invest in should help you understand how wrong you could be to rely only on extrapolation.

And finally, utilizing diversification and longer investment time horizons both work in your favor.

Did you enjoy reading about extrapolation bias? To learn more about investing, don’t miss out on our Masterclass E-Mail Series. Sign up for free.

Disclaimer: The content of any publication on this website is for informational purposes only.