Investors can enter the markets in a variety of ways. Depending on their preferences, they may choose to make one lump-sum investment, invest gradually and regularly, or… wait for the moment at which the markets reach their lowest. We’re about to explore the real-life consequences of each strategy.

To test each of these strategies, we’ll be assessing the daily return on investment of CHF 100’000 into the Swiss equity benchmark – the SMI (Swiss Market Index).

We’ll run experiments based on varying periods of time, and from the perspective of four groups of investors:

- The first group will invest the full amount at the beginning.

- The second group will invest CHF 10’000 every 30 days until CHF 100’000 is invested.

- The third group will try to predict the market (which we’ll replicate with a random group of 100 investors who enter and exit the market ten times over the period).

- The fourth group will invest part of the capital (CHF 10’000) whenever they see the market drop by a minimum of 2.5% in one day.

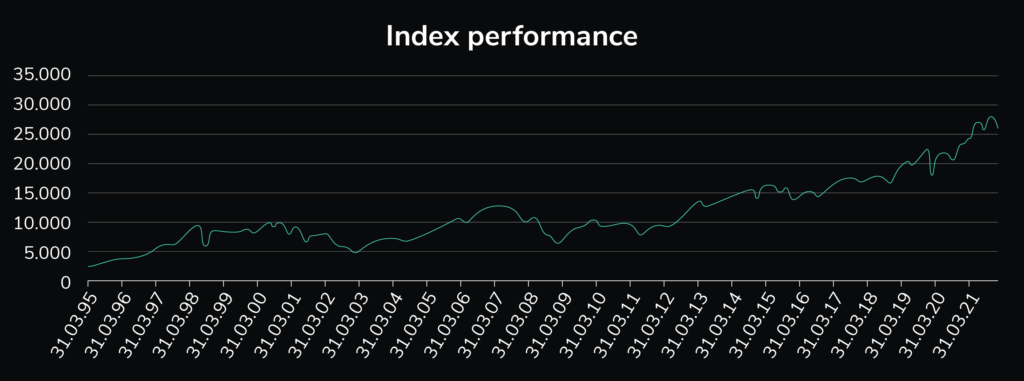

Graph 1: Evolution of the Swiss Market Index prices from February 1995 until February 2022.

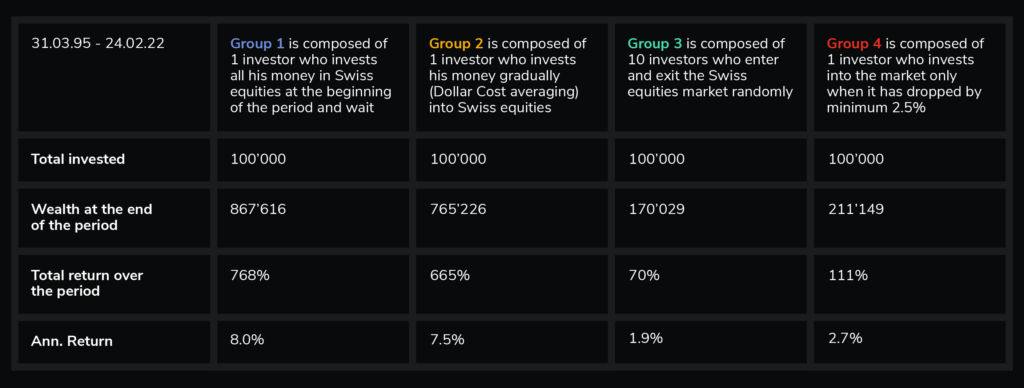

We observe the following results from March 1995 until February 2022:

Table 1: Evolution of an investment of CHF 100’000 for four different groups of investors in the period March 1995 – February 2022, adopting strategies of “buy and hold”, “Dollar Cost Averaging”, “Random Market timing”, “Waiting for a minimum drop of 2.5% before investing”.

It’s apparent that Group 1’s method outperforms the others over the long term. Group 2’s dollar-cost averaging strategy also achieves an attractive positive return. By contrast, the investors who tried to anticipate the market had a smaller annual return, and those who invested after market declines of more than 2.5% (Group 4) had only a slightly positive average annual return.

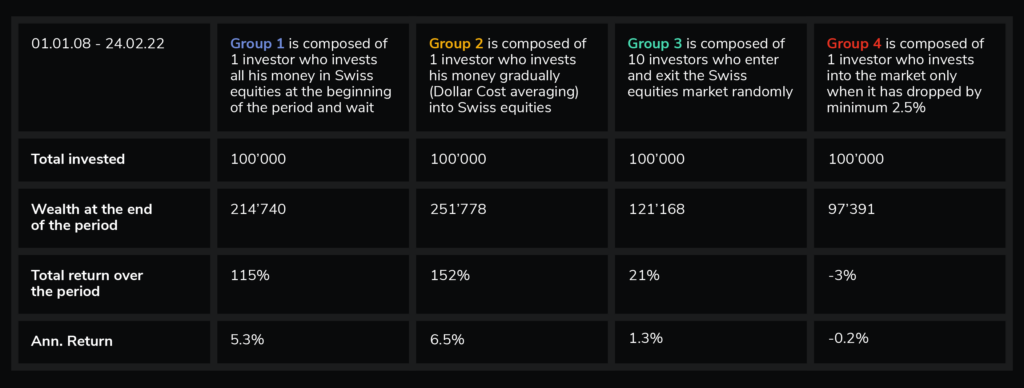

Let’s look at the same model over a shorter period that includes the 2008 financial crisis – January 2008 to February 2022:

Table 2: Evolution of an investment of CHF 100’000 for four different groups of investors in the period January 2008 – February 2022, adopting strategies of “buy and hold”, “Dollar Cost Averaging”, “Random Market timing”, “Waiting for a minimum drop of 2.5% before investing”.

Of note is that Group 2’s performance has improved – because they were the least affected by the 2008 crisis. Group 4 had a negative return because it was fully invested at the beginning of the crisis and could not continue to invest as prices plunged.

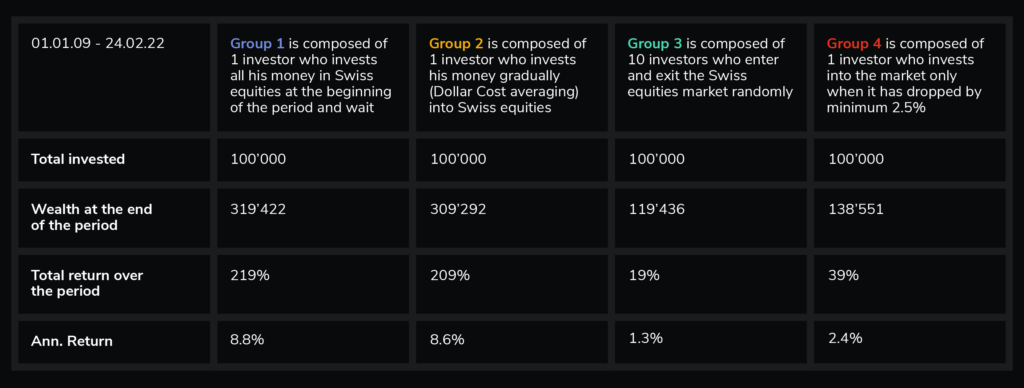

Then, let’s examine a slightly shorter period – January 2009 until February 2022:

Table 3: Evolution of an investment of CHF 100’000 for four different groups of investors in the period January 2009 – February 2022, adopting strategies of “buy and hold”, “Dollar Cost Averaging”, “Random Market timing”, “Waiting for a minimum drop of 2.5% before investing”

Again, Group 1 has performed the best, closely followed by Group 2. Group 4 missed the entire bull market because of its strategy.

To conclude, we see that

- The “all-in” approach (Group 1) appears to be the best option both over the long-term strategy and for purely capitalizing on rising markets.

- During turbulent periods, “Dollar-Cost Averaging” (Group 2) is attractive because it reduces the impact of short-term volatility without forcing one to wait for the “perfect” moments. In a way, it mitigates risk. But if turbulent times are followed by rising markets, these investors miss out on lots of upsides, as they will not have invested the entirety of their money. The investors also have a risk to miss on the uptrend and being fully invested when the market goes down.

- Market timing (Group 3) appears to be on average a losing strategy, at least for random entrances and exits of the market.

- Group 4’s strategy seems interesting in theory, but difficult to apply. Because the investor must wait for market downturns, there’s a large chance of missing out on upswings. It’s also difficult to predict how much should be invested in each downturn because no investor knows how many downturns will occur over their investment period.

Footnotes:

* As a general rule for dollar-cost averaging, the further apart the increments and the smaller the amounts, the more successful an investor will be in smoothing out volatility and purchase price.

** Within the framework of a management mandate, the more aggressive the investment strategy (with a high percentage of equities), the less lucrative the dollar-cost averaging will be. Indeed, it means taking the risk later and delaying an entry into the markets

***

Disclaimer:

The content of any publication on this website is for informational purposes only.